Leaving a Trace is about supporting those who want to become more aware of other species’ perspectives within urban environments. As we expand and develop our living spaces, urban spaces have the opportunity to become less human-centred, and take into account the other species that share the space with us [2, 7]. Facilitating this shift will require more than just expanded ecological knowledge, but a shift in a way of thinking for designers that may not have previously considered other species in their design process or outcome.

This project is concerned with equipping designers with the tools and methods to make use of their skills within their practice. The aim of the project is to support designers in developing their way of thinking in relation to the ecosystem. Tackling this ‘perspective gap’ between designers and ecologists encourages them to consider not only their impact but their relation towards an ecosystem and the species within it.

There are two main components to the project, sketching and environmental monitoring. Together these activities help to develop the user’s biodiscovery, biocuriosity, and bioliteracy [3].

Observational sketching necessitates a certain level of focus that is uniquely suitable for the “arts of noticing” [8], inspired by Anna Tsing. Noticing refers to the raising of your attention or awareness to other perspectives that may have previously been overlooked or marginalized. In order to sketch a landscape, the observer must carefully decide what to put down on the page, this act reveals not only what they were looking at, but what they saw (or didn’t). Breaking this down further can lead to insightful reflections on your own perspective on an environment, something which can dynamically evolve as you carry on this journey. In addition, sketching takes more time than taking a photo, requiring the user stay in the space for 15 minutes or more, which is usually the time needed for animals to come out of hiding and become comfortable with your presence.

Sketching a plant or animal can teach you a lot, but it doesn’t necessarily mean you will understand its lifecycle, biology or its trophic level. Moreover, other species may be more sensitive to certain environmental conditions that are difficult or impossible for humans to pick upon. This is why the sensor kit is introduced, it can collect data on temperature, humidity, TVOC levels, CO2 level, UV, soil moisture and soil salinity. In addition to the sensor kit, identification apps like iNaturalist aid in developing the user’s bioliteracy and providing a way to conduct further research on the species’ ecology [3]. An ecologist involved in the project commented on how the collection of ecological data can help to nudge the user to consider the relevance of multispecies perspectives. For example, if you are wondering now why CO2 levels are important to keep track of, this may lead to you investigating and learning why the species in your area are sensitive to CO2 changes. In this way, a ‘relational perspective’ is established. This can help the user to decentre themselves and instead put their relation to other species in the centre of attention when designing.

Beyond the observational and analytical activities, the process also includes a creative and imaginative aspect. If the sketching can reveal something about your own perspective, what could it reveal about other species’ perspectives? Sketching is also used to imagine this, playing with scale and abstract images, such as placing tiny human figures in an environment, reframing the space and its possibilities instantly. While partaking in this process, you will quickly realise that it simply isn’t possible to imagine exactly what the perspective of another person is, let alone another species. However, the point is to make the attempt, and through this understand the distance between you and the other possible ways to experience the space other than your own. What’s more is that the imaginative sketches can lead to new ideas about what you want to do with the space, how your project can interact with the ecosystem or perhaps even regenerate it. Let the creativity flow.

It’s not just about what data is collected, but about how it’s collected.

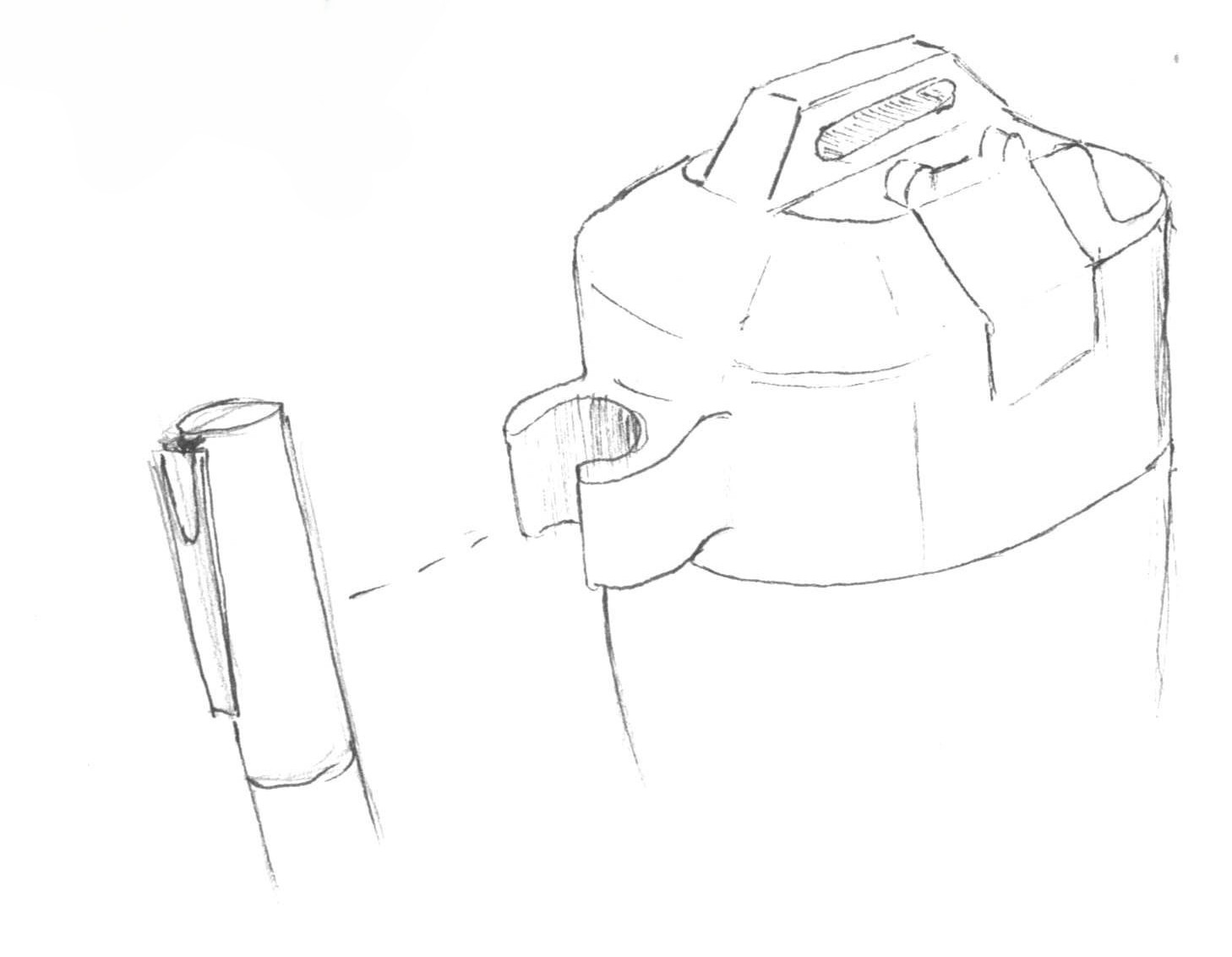

Accessibility of the design refers to removing barriers to other designers who want to engage closer with their environments. An open-source design already accomplishes a lot in bringing tools within reach of a wide community. Not knowing where or how to begin is likely to prevent many from trying as suggested by participant interviews. Naturally, affordability plays a role in this too, as most available options tend to be either expensive industrial grade products or cheaper prefabricated kits for indoor monitoring. Producing the casing through 3D printing expands the accessibility, fitting right alongside many open-source projects.

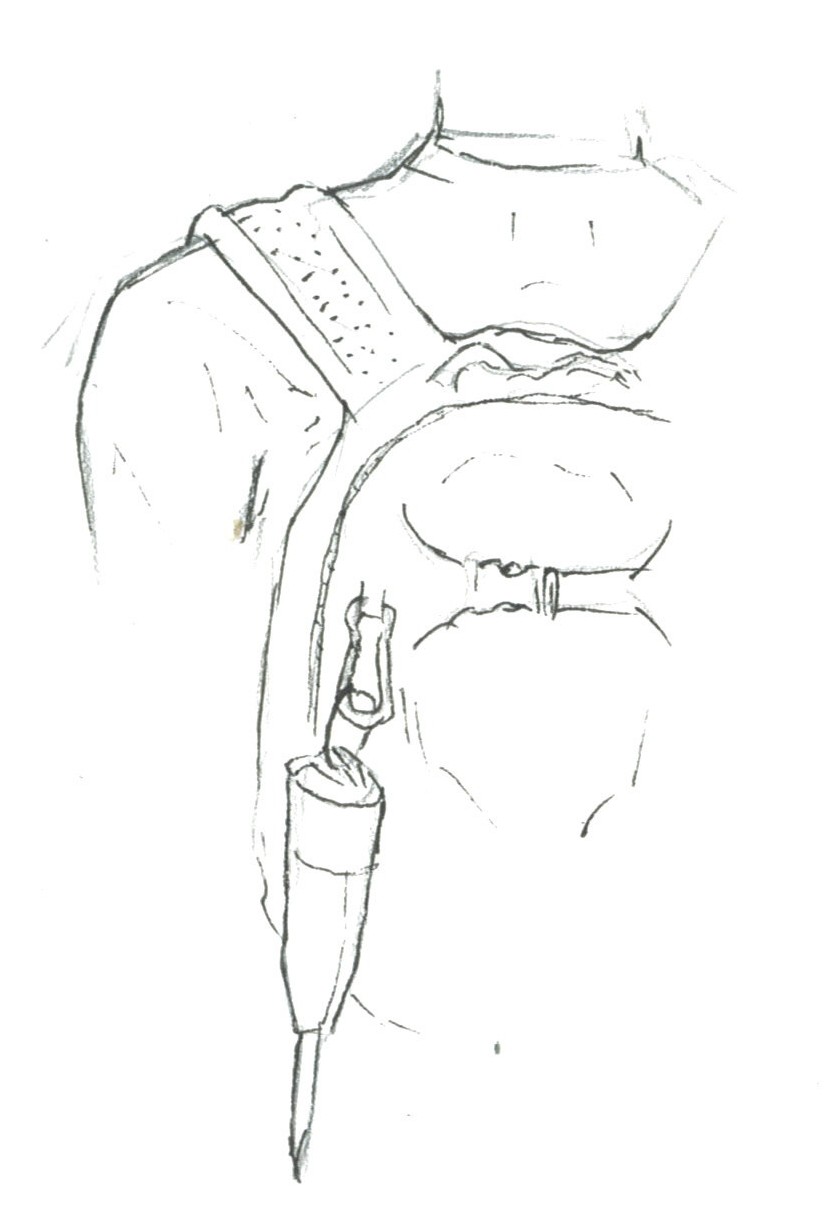

Having at least one hand free while heading to the environment or walking around within it is conducive to a more seamless user experience. It further reinforces that the tool can be taken where the user wishes without being burdened by a lengthy or intensive transportation or installation process. It aesthetically also aligns with other handheld tools in the designer’s toolkit.

In many ways, the tool is like a starter kit for ecological data collection. Not every environment or species will be affected by the conditions the current kit collects, other sensors may need to be replaced for new sensors, perhaps for gas sensing for example. This is reflected in the choice of the ESP32, meaning the user can still upload adjustments themselves and make use of other functionality like Bluetooth if they wish. Making the casing as a 3D printed part similarly means the model can be easily adjusted to include other sensors. Minimal soldering and the use of reversible connections with jumper cables further lowers the threshold for the customisation process.

The design offers a few interaction styles. Short term monitoring, done after and during sketching can quickly probe several places in an environment. Longer term monitoring when the designer is not there is equally possible. Reproducing the tool multiple times offers even more monitoring styles.

If you are curious to learn about this project’s inspirations, here are some interesting papers and books that guided me along the way:

A helpful overview of technology mediated nature engagements:

Engaging with Nature through Technology: A Scoping Review of HCI Research [10]

Main inspirations for designing a tool:

Design and Deploying Tools to ‘Actively Engaging Nature’ [6]

Design for Collaborative Survival: An Inquiry into Human-Fungi Relationships [5]Urban landscapes and ecosystems:

Novel urban ecosystems, biodiversity, and conservation [4]More-Than-Human Participation: Design for Sustainable Smart City Futures [2]

Noticing

The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins [8]

Ecological Thinking

Watching Myself Watching Birds [1]

Cohabitation

Designing for Cohabitation: Naturecultures, Hybrids, and Decentering the Human in Design [7]

More-than-Human Design

Things We Could Design: For More Than Human-Centered Worlds [9]

Youp Ferket is an industrial designer from the Netherlands, having recently graduated from Eindhoven University of Technology. He has a background in user-centred design methods, elevated by recent academic work focusing on more-than-human design.

06 18856778yferket@gmail.comwww.linkedin.com/in/youpferket

[1] Heidi R. Biggs, Jeffrey Bardzell, and Shaowen Bardzell. 2021. Watching Myself Watching Birds :Abjection, Ecological Thinking, and Posthuman Design. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445329

[2] Rachel Clarke, Sara Heitlinger, Ann Light, Laura Forlano, Marcus Foth, and Carl DiSalvo. 2019. More-than-human participation: design for sustainable smart city futures. Interactions 26, 3: 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1145/3319075

[3] Colleen Hitchcock, Jon Sullivan, and Kelly O’Donnell. 2021. Cultivating Bioliteracy, Biodiscovery, Data Literacy, and Ecological Monitoring in Undergraduate Courses with iNaturalist. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 6, 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.439

[4] Ingo Kowarik. 2011. Novel urban ecosystems, biodiversity, and conservation. Environmental Pollution 159, 8–9: 1974–1983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2011.02.022

[5] Jen Liu, Daragh Byrne, and Laura Devendorf. 2018. Design for Collaborative Survival: An Inquiry into Human-Fungi Relationships. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173614

[6] Robert Phillips, Amina Abbas-Nazari, James Tooze, Bill Gaver, Andy Boucher, Liliana Ovalle, Andy Sheen, Dean Brown, Naho Matsuda, and Mike Vanis. 2019. Design and Deploying Tools to ‘Actively Engaging Nature’: The My Naturewatch Project as an Agent for Engagement. In Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Design for the Elderly and Technology Acceptance, Jia Zhou and Gavriel Salvendy (eds.). Springer International Publishing, Cham, 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22012-9_37

[7] Nancy Smith, Shaowen Bardzell, and Jeffrey Bardzell. 2017. Designing for Cohabitation: Naturecultures, Hybrids, and Decentering the Human in Design. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1714–1725. https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025948

[8] Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing. 2015. The mushroom at the end of the world: on the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

[9] Ron Wakkary. 2021. Things we could design: for more than human-centered worlds. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts London.

[10] Sarah Webber, Ryan M.Kelly, Greg Wadley, and Wally Smith. 2023. Engaging with Nature through Technology: A Scoping Review of HCI Research. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581534